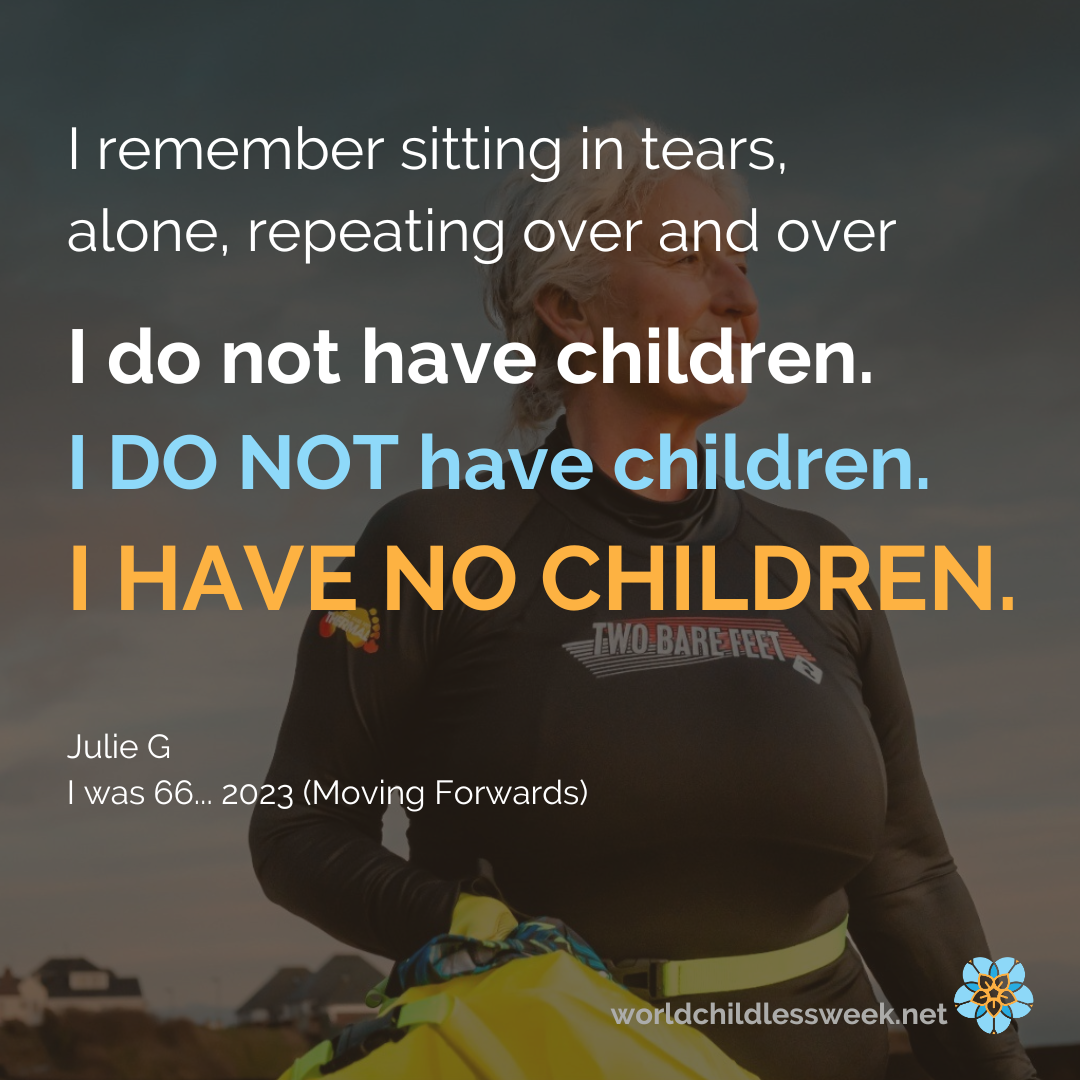

Julie G

I was 66 when I suddenly realised I didn’t have children.

That sounds ridiculous, I know. I feel a bit embarrassed admitting it.

But the realisation was, obviously, not a sudden revelation that I had imagined that I did have children and suddenly saw the truth. It was more that I had gone through so many years not having grieved at all for my childlessness. I had grieved my miscarriages, I had grieved my broken relationships but I had never seen clearly how much of my energy and focus had gone into trying to achieve a ‘normal’ life, with a partner and a family.

And even when I was beyond the age of fertility, I hoped that perhaps I’d meet someone who would share his family with me, his children and maybe grandchildren. I almost got there once.

I knew how much of an outsider I felt. I knew how hard Christmas, holiday times were. I knew I was the only one of my siblings not to have had children. And that however much I tried to be an important part of my nephews’ and nieces’ life, somehow something - largely one of my siblings - got in the way.

But it was only once I’d found my tribe in Gateway Women, as it then was called, and the overwhelming understanding and empathy that it brought, that I felt safe enough to really accept my childlessness. And to really grieve that huge loss.

I remember sitting in tears, alone, repeating over and over ‘I do not have children. I do not have children. I have no children.’

But no one laughed or made fun of me. Many others had lived decades, unable to articulate or express what was happening in their lives, only able to live it as best they could.

No one had said to me; ‘Julie, this depression, this search for meaning, this despair, this existential, utter loneliness, are because of the losses and absences you have suffered, and that you endure, even still.’

It was as if childlessness was a dirty word. ‘We assumed you didn’t want children’. I can’t blame them, much as I’d like to.

In my fifties, hysterectomy came, and even then I didn’t realise. No one helped. I said something to my GP about dwelling on the loss and she said ‘perhaps it’s better if you don’t dwell on it’.

I remember hearing the term ‘pronatalism’ soon after I got involved with GW and asking what it meant. I need words. It makes things more real if they’re expressed in words. And once I knew what pronatalism meant, I saw it everywhere, and it explained so much. It had been the water I swam in - somehow, despite living through the 1970s as a young woman, despite my MA in Women Studies, that term had never come to my attention. In so many contexts, being a mother is so much a ‘given’. Unquestioned.

And now I live with a simmering anger. I can be nice! I can relax. I can be kind. And so on.

But I won’t put up with being the quiet recipient/listener to some woman’s stories about her children or grandchildren, unless they happen to be involved in something I’m interested in anyway.

I really love cutting off their oxygen. To my amazement, I can allow silence, I can NOT respond, I can give no cues at all for them to continue their stories. As soon as they take a breath, I will jump in with a change of subject. Rude? Is it any ruder than selfishly forcing unwanted monologues on a relative stranger?

But I can do this because I’ve moved through some of my grief. I still hurt. I can still feel like the odd one out. I’ve learned to say ‘no’ to things that will make me too uncomfortable, and to walk away as soon as the discomfort arises.

Many people of my age have lived enough to have learned that not every life follows a planned or conventional trajectory. So, if I choose, it’s not so hard to say ‘it just didn’t happen, sadly’. Or something similar.

And when the thoughtless comments or questions come, I find I’ve strengthened enough from my precious LW tribe to feel more resilient. I’m not alone.

I’m building a life worth living. The things I do are important to me. And they evoke in me a passion and care that feel akin to maternal love.

I remember once at a very left-wing gathering, the speaker talked about the suffering of children in other countries. and he declared ‘they are all our children’. And they are.