Aven Kane

There are apparently three metrics to a healthy sperm sample: volume, motility, and morphology. The first factor is easy enough to wrap your head around; the goal is at least 1.5mL of ejaculate per sample, with a concentration of 39 million sperm or more. Motility is also reasonably straightforward: at least 32% of the sample should be actively moving when you view it under a microscope to ensure there are enough swimmers to potentially fertilize an egg. Finally, morphology confirms that at least 4% of the sperm are shaped correctly, with one head, one tail, and no evidence of additional growths or disfigurements.

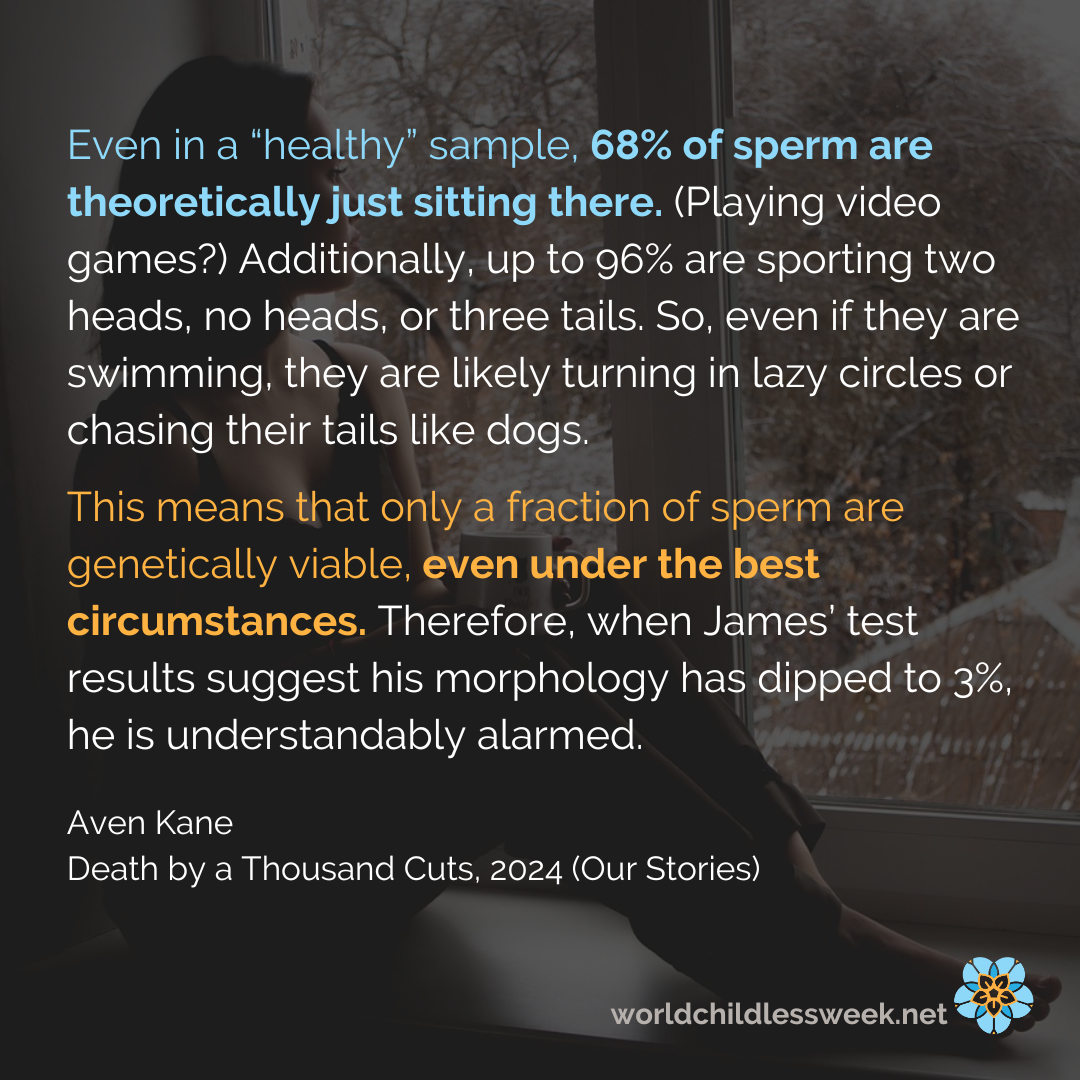

While you wait for your husband James’ test results, you marvel at the incredibly low bar you have just identified for male reproduction. Even in a “healthy” sample, 68% of sperm are theoretically just sitting there. (Playing video games?) Additionally, up to 96% are sporting two heads, no heads, or three tails. So, even if they are swimming, they are likely turning in lazy circles or chasing their tails like dogs.

This means that only a fraction of sperm are genetically viable, even under the best circumstances. Therefore, when James’ test results suggest his morphology has dipped to 3%, he is understandably alarmed.

You are, too. Since uterine conception relies on the ability of James’ sperm to reach your egg, a 4% morphology rate is the cut-off for IUI. This means James’ morphology numbers may have just fast-tracked you both to IVF.

Only… maybe not quite so fast. Because James’ results are nearly viable, your doctor offers to retest him in a month. And your husband, to his credit, spends the next 30 days purging anything that could be considered unhealthy from his life. He gives up alcohol and caffeine, begins taking cold showers, and even forgoes his usual long-distance bike rides in favor of calisthenics in the backyard.

The ease with which James sacrifices some of his greatest pleasures demonstrates his commitment to fatherhood more clearly than any other challenge he has confronted so far. It also doubles down your resolve to hold up your end of the bargain. Accordingly, an expensive new vitamin routine begins to supplement your mornings. You buy a book about PCOS, say goodbye to processed foods, and pledge to prioritize clean eating.

You are no stranger to existential questions, so it feels natural to shift into a supporting role when James begins questioning his life’s choices. Did he spend too many hours training for Ironman races? Did he party too hard in his twenties?

You are grateful to be there for James, to provide comfort the way he has sometimes comforted you. However, as much as you wish you could deny it, another emotion thrums beneath your altruism: one that leaves your insides quaking with a mixture of comfort and guilt.

Is it terrible to admit that a tiny part of you feels relieved that you aren’t the only one with a medical diagnosis? It’s not that you wish this turmoil upon James, not by a long shot. You would like to say you would even take away his anxiety if you could. But is that true?

Deep down, in the shadowy recesses of your being, haven’t you been harboring an unreasonable amount of guilt over being the ‘broken one?’ And although he has never come right out and said it, isn’t a tiny part of you grateful that James can no longer speculate that humanity can overcome any obstacle put in their way by simply invoking the ‘power of positive thinking?’

You don’t express these feelings to James right away. However, you eventually confess your relief that you no longer have to shoulder the burden of ‘being the broken one’ alone. “I’ve just been feeling like, if we weren’t able to have kids, part of you would resent me for the rest of your life.”

James has never insinuated he blames you for your setbacks, so your confession likely startles him. Even still, the recognition that you now stand on a somewhat even playing field with him secretly comforts you. It is one of many tiny checkmarks you add to the subconscious scorecard you didn’t realize you had begun keeping.

‘Death by a thousand cuts’ is an expression that will resonate when you revisit the injustices James and you experience during this time. Would a better person have been able to navigate similar turmoils without embedding her own shortcomings and insecurities into the fray? Would a less selfish person have been able to remain genuinely benevolent in the face of such trials?

Is the failure truly yours? Or is it the failure of a system built to confront the mechanics of infertility while never accounting for the imprint such an experience may have on its participants? Is the answer somewhere in between?

Further, once the desperation begins to creep into your life, how much blame do you bear for allowing some of that darkness to seep inside and poison you?