Claire

I finished reading her favourite story, tucked her duvet gently around her and handed her the teddy bear that had been her companion since she was a baby. She settled it in the bed beside her then looked up at me with her big blue eyes, her young face suddenly serious. ‘Why aren’t you a mummy?’ she asked.

I felt my chest tighten.

I was used to being asked whether I had any children. A seemingly innocuous conversation opener if you’re a parent. A place to find common ground with the stranger in front of you. An emotional grenade being thrown in your direction if you are childless not through choice, but one thrown so many times that, more often than not, you can see it coming. You brace for impact, push your own feelings to one side for the sake of not making the other person uncomfortable, and invite the conversation that you don’t want to have.

‘No, do you?’

When we meet new people, even when making small talk, we place value judgements on them. It may be consciously, it may be subconsciously but we’re looking to learn more about them, to determine whether we should be investing our time in them. Why though, in that moment, do we place so much importance in what they do for a living or whether they have children? Imagine what we could learn about someone in our first interaction with them if we asked which book, song and film they would take to a desert island with them or found out which decade they would travel back to? Maybe it’s time we changed the narrative?

‘Why aren’t you a mummy?’

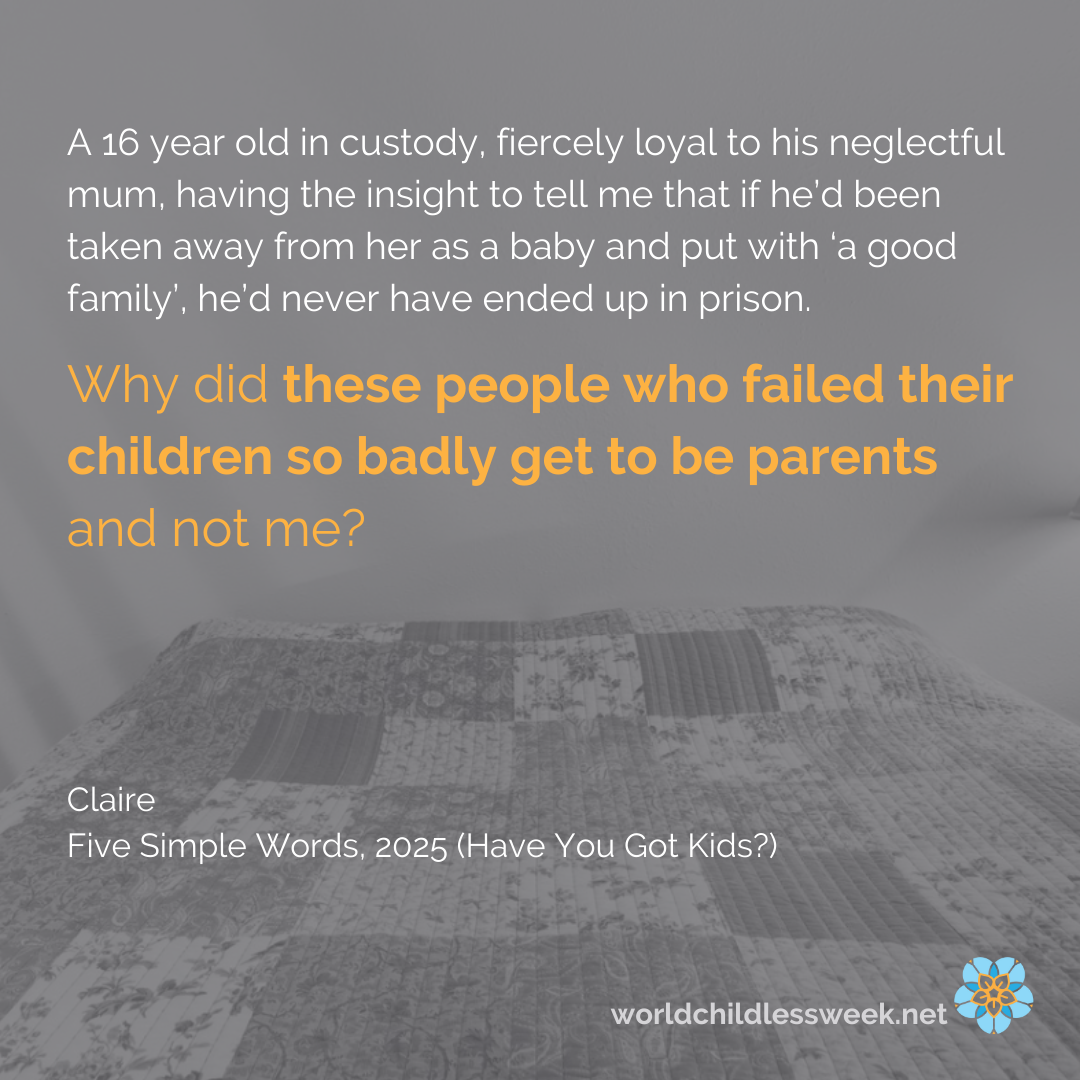

Much of my career has been spent working with vulnerable young people and I have witnessed some of the worst parenting that you can imagine. Neglect, aggression, substance misuse. Teenagers, damaged by their childhoods yet still resilient. A 16 year old in custody, fiercely loyal to his neglectful mum, having the insight to tell me that if he’d been taken away from her as a baby and put with ‘a good family’, he’d never have ended up in prison.

Why did these people who failed their children so badly get to be parents and not me?

Every time the news reports on a celebrity having a child later in life or someone shares a photo of themselves enjoying a summer holiday with their children, or in matching pyjamas in front of a Christmas tree, I can’t help but think why didn’t I get to be that person too?

I used to believe that the why was because my path to parenthood would be different. Fostering isn’t right for everyone but it felt right for me. I knew that I could provide an older child, the most difficult to place, with the support that they needed to see them safely through the transition from teenager to adulthood but I was up against a system that would fail me and those children. One that would rather pay a private provider to keep a teenager in an expensive care home than assess the suitability of someone with years of experience working with disenfranchised young people, simply because their work meant that their salary was not enough to afford the rent on a 2 bedroom property. Rent that they would be able to afford if assessed as suitable and a child was placed with them.

‘Why aren’t you a mummy?

What was it about those five simple words that had hit me so hard? Perhaps it was the sense of validation that they brought. The feeling that she recognised in me qualities that she saw as being central to motherhood. The antithesis to what you endure being childless in a pro-natal society where so many of those around us, particularly in politics and in the media. view parents as being more compassionate, more empathic, more invested in others. More worthy.

‘Why aren’t you a mummy?’

Her question needed an answer but my story was one that I would never share with her. One that I’ve never fully shared with anyone. A patchwork quilt that spans a lifetime. Each square forming a part of the narrative. A health diagnosis that came too late, a drunk driver, a reproductive system that called time too early. Chances missed and roads not taken. The silver thread of hope that once held the pieces together, now grey and faded.

‘Why aren’t you a mummy?’

I smiled, the mask I so often wear readily accessible to me. ‘ I hope to be one day’. I replied, because in that moment, as with the story that I had just read to her, this story needed its happy ending too, even if such an ending would only ever be a fairytale.

She’s a young adult now. Her own quilt a blank canvas that I hope is filled with colour from memories made during relaxed summer days, and nights spent dancing until the sun rises. Of friends that will be her anchor and of adventures and experiences that will fill her soul with joy.

As for me, if someone asks me now whether I have children, I’m at peace with the silence that my answer will create.

‘No’. I’ll reply. ‘I wasn’t that fortunate’.