A one hour webinar with Jody Day, Founder of Gateway Women on 'Finding Acceptance & Moving Forward' recorded live for World Childless Week 2018.

Read moreFinding Acceptance and Moving Forwards, links we love

Throughout the weeks to come and starting from today, we've compiled the links to sites who are also sharing content that the team and Champions think you'll love to read because the creator writes to our daily theme.

Read moreWalk In Our Shoes and World Childless Week by Berenice Smith

I wanted to share the video that I made after I spoke at Fertility Fest’s More to Life event. It’s not the live feed but one I recorded at home with a voice over. I hope it explains to you why World Childless Week matters to me and why going off and studying a Masters was the best therapy for me!

Survey Results for Moving Forwards and Finding Acceptance

Do you feel acceptance is a relaity?

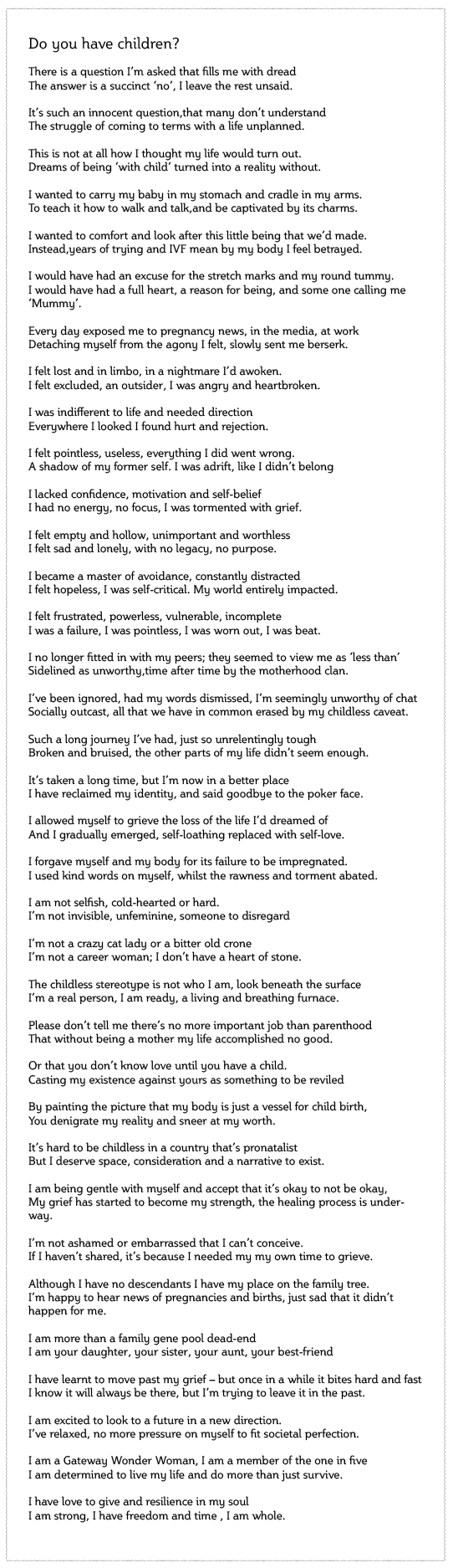

Read moreDo you have children?

There is a question I’m asked that fills me with dread

The answer is a succinct ‘no’, I leave the rest unsaid.

Read moreOMFG, I’m complete and utter failure 'cos I can’t make babies!!

A pretty bold statement to make right? Those who know me well, will appreciate I am partial to the odd exaggeration! However, ask my husband Rich and he’s heard me wail that many times over the last few years in my lower, darker moments during our 5-year fertility journey.

Read moreOne woman’s journey through childlessness - Meriel Whale

Grief-stricken and hopeless

I’m sitting on the floor of the bathroom, it’s 2 am. I’m crying, but very quietly, so no-one can hear. After a few minutes, I make myself stop, because after all, what’s the point?

Read moreProject Me

Throughout my life I’ve struggled with eating. I’ve been dramatically under and overweight but my body image always places me as fat, ugly and childless. It’s the thing that I worry about after infertility in the early hours of the morning. It stops me standing on stages, going to events, meeting people and seeing my family because I feel that they judge my weight. I know that some people do because I hear and see them.

Read moreI get to choose by Carol G

The journey of being childless not by choice has many twists and turns, detours, and dead ends. There are so many choices to be made along the way about how we react to the heartache of being childless not by choice, and who we develop into.

I want to share what I have learned so far, in the hope that it can be a help to others.

Read moreLesley Pyne, a zoom chat and book reading

Hello, I’m Lesley Pyne, author of ‘Finding Joy Beyond Childlessness; Inspiring Stories to Guide You to a Fulfilling Life.’ I’m really excited to be involved in World Childless Week especially today, Acceptance and Moving Forward.

Read more‘A child of all life’: creativity and re-imagining life without children by Emma Palmer

Years ago when I was in the midst of writing ‘Other than mother’, my second book, I started to find that my writing was grinding to a halt. It was a gradual thing; a painful, murky thing. It wasn’t that I couldn’t write, and it wasn’t that I was short of things to say, it was more of a sense of the impossibility of writing about being without child. Like being in front of a very tall brick wall. Or facing a giant STOP sign. Feeling immobilised, with a groaning, silent sense of lack - with a capital L.

I could no longer write about something I wasn’t doing in an active, engaging way. It dawned on me - again, a gradual thing - that this writing, this little evolving work of art, had to be about what I was doing, what was happening and juicy and life-affirming rather than what I wasn’t doing. In short, it had to be about life in whatever form life takes in that moment or on that day, week, or month.

This was an important turning point for me in so many ways. It made me realise how being without child, for whatever reason, in the world we’re in, has the capacity to ‘shroud’ many of us in a sense of lack, feeling or being seen as lesser, invisible, and rather voiceless.

I had fallen, unknowingly, into a trap, imbibing that lack and the feeling of being less. My writing almost ground to a halt and I nearly gave up writing ‘Other than mother’ (I’m very glad I didn’t.)

I woke up one morning and realised what was happening. I saw the shadowlands I had visited or had visited me and my self-doubt. It was very useful - sober-making, too - in terms of the book’s content, to experience first-hand the stereotypes, assumptions and views about those of us without child, amplifying the fact that we’re without children whilst neither paying attention to, nor honouring the many other areas of our lives where we’re most definitely not lacking. The old chestnut of being defined by our procreation in a still overwhelmingly pro-natal society.

I also realised I had to re-orient the book around what I was doing with my life, expressing abundance, richness, and in doing so, becoming visible. For this book, and as a woman who is generally identified as someone who’s child free by choice - if I must be categorised! - I realised the book needed to focus on the choice to be childfree, reflecting my own situation at the time. For me it needed to be about life beyond being without child, a territory I hadn’t let myself envisage before then, perhaps still stuck in struggling to conceive of a life without children.

Figuring out life when you’ve always imagined you would be a parent but you’re not is a big one. It’s been a big one for me, and I’m childfree by choice. I see around me how it’s a huge, heart and life-wrenching process for those of you who imagined motherhood or parenthood, who longed to welcome children into your life, or who have had children who’ve died or didn’t make it to their first breath.

For me that figuring out has been far far less charged, far less painful and raw, as I’m childfree by choice. Having said that – and in no means discounting the scale of that loss - I

often find myself writing that I personally and increasingly think that there are vast grey areas between those of us who are without child by choice, circumstance, loss, ambivalence. It’s not really black and white territory for most folk. In the words associated with Jo Cox, the late labour MP there is often 'more in common than that which divides us'.

And I think, going back to the writing story I opened with, that all those turning points when we moved towards life, towards creativity - however you express that in your life - and away from that groaning, lonely, silent sense of lack - are life-changing. Sometimes life-saving, in fact.

I’ve experienced a fair amount of grief in my life, some very early on. I know the tsunamis, the troughs, peaks and then the prolonged numbness of watching my life as if I’m an actor on a stage: ‘is that really me living life? I can’t feel it’... then, suddenly, I’m flipped upside down with another tsunami, the stage swept away. I’m feeling everything all at once.

I haven’t, however, grieved for a child I couldn’t or wouldn’t be having. Nor for a child I lost. I have been with friends and psychotherapy clients and colleagues who’ve been through this. I support as much as is humanly possible. I sometimes see folk come through this with phenomenal strength, embodied strength – strength in their bone marrow - rather than an idea of strength. And an appreciation of the great preciousness of life.

I personally don’t think time is automatically a healer. I sense that turning back towards life, edging back, sometimes breath by breath - wherever our starting point - is what heals. We turn towards life and its inherent creativity. Death and destruction are over our shoulders. They’re there because death is part of life and life is part of death, but they’re no longer the only thing we see ahead. There are metaphorical ‘GO’ signs ahead of us, even if on the far horizon. Maybe we find out feet and walk forward.

I found my feet walking forwards, or, rather, my pen starting to flow again when I realised I needed to turn towards the reality of creativity and life after the choice not to have children – deeply challenging to me and my ‘I’ll be a mother one day’ identity for more than the first two and a half decades of my life. Part III of ‘Other than mother’ reflects that return to creativity. My intention in writing it was to explore how life can take so many forms which don’t involve the creation of a little human. Creativity takes so many forms. In writing that part of the book I realised for myself what I needed to connect, or re-connect more deeply with life: re-imagining what life looks like at 40 (and 50, 60, 70, 80…), gently letting go of old expectations (‘I’ll have children by the time I’m 30’, I would tell myself repeatedly), giving and receiving support from others, whether without child through choice, circumstance or loss, creating new traditions, new rites of passage for those without child.

The great Gary Snyder, American poet, essayist, and environmental activist puts it well:

"I am a child of all life, and all living beings are my brothers and sisters, my children and grandchildren. And there is a child within me waiting to be born, the baby of a new and wiser self" (Snyder, G. (1995) A Place in Space: Ethics, Aesthetics, and Watersheds. Counterpoint Press).

Beyond the C Zone... Moving Forward through 40 Challenges

Fast forward to 2018, the year I turned 40, the number I’d always seen as the final cut off age to fulfilling my dream of becoming a mum. I felt stuck and knew something had to change if I wanted to beat the roadblock.

Read moreRosalind Bubb - Easing the pain of being childless, using EFT 'tapping' video

Would you like a simple and effective self-help tool, which you can use to help you to change the way you feel about being childless? - one which can reduce and soften the painful emotions, right now?

Read moreNaming Your Grief by Jennifer Parrish

It is so strange to me that I am writing something about finding acceptance and moving forward from my childlessness. You see, I never thought I’d be here in this place . . . Whenever I’d see stories of women who were moving forward from their childlessness, I was always so jealous—I wanted to be in that spot, yet I had no idea how to do it!

The turning point for me came after I saw a post on Facebook from a fellow CNBCer back in January. She read a book about infertility and the author suggested naming your grief. For my friend, that meant naming the children she would never have. That touched a nerve with me and I knew I had to do the same!

I talked to my husband about it that night and he thought it was a good idea, too. So we discussed names and decided to name our prayed-for son and daughter. We named our son Benjamin Wright and our daughter Diana Rose. It felt so good to give them a name even though we never held them or ever carried them in my womb. We knew them in our hearts and naming them gave us both peace. It gave our grief a name and gave us something tangible to hold on to whenever we thought about the children we would never have. Now, they have a name—an identity. And our grief finally had a name and an identity.

Since we named our pray-for babies, I have grown in leaps and bounds in finding acceptance and moving forward. I definitely still have bad days, but the good days are now outweighing the bad. I am allowing myself to grieve and to feel all the feelings associated with that. I am finding joy and peace even in my childlessness.

I am finally learning to live in that place between the grief of childlessness and the joy of a life well-lived!

Week fifteen: a letter to motherhood ‘Mo’ - Elizabeth Broadhurst

I wrote this 15 weeks after my hysterectomy

Read moreLife after childlessness by Victoria

Moving forward, moving on, getting over ‘it’, coming to terms with ‘it’’, are just some ways my infertility has been described. It has never been labelled and has in some ways been brushed under the carpet and doesn’t get talked about.

Well I have now got to a stage in my life where I can now talk about my childlessness, why I don’t have children and how my life has now evolved.

Read moreAnd then one day joy showed up - A personal journey through grief

I woke up one day and found that 6 years of my life had passed. Passed in a haze of sadness, exhaustion and despair. I had aged, white hairs had shown up, and life had moved on, seemingly without me. Friends had grown tired of waiting for me to come out of hibernation and had slowly, gradually stopped calling or inviting me out. It felt like stepping out of a deep dark cave into bright sunlight, it felt overwhelming and I wasn’t quite sure where to begin.

Read moreFinding Acceptance & Moving Forwards introduction by Stephanie Phillips

Today is not only about Moving Forwards and Finding Acceptance; today also falls on the 16th September which last year we claimed as our day.

Read more